Cambay, Idar-Oberstein, Czechoslovakia and France Volume 46.3

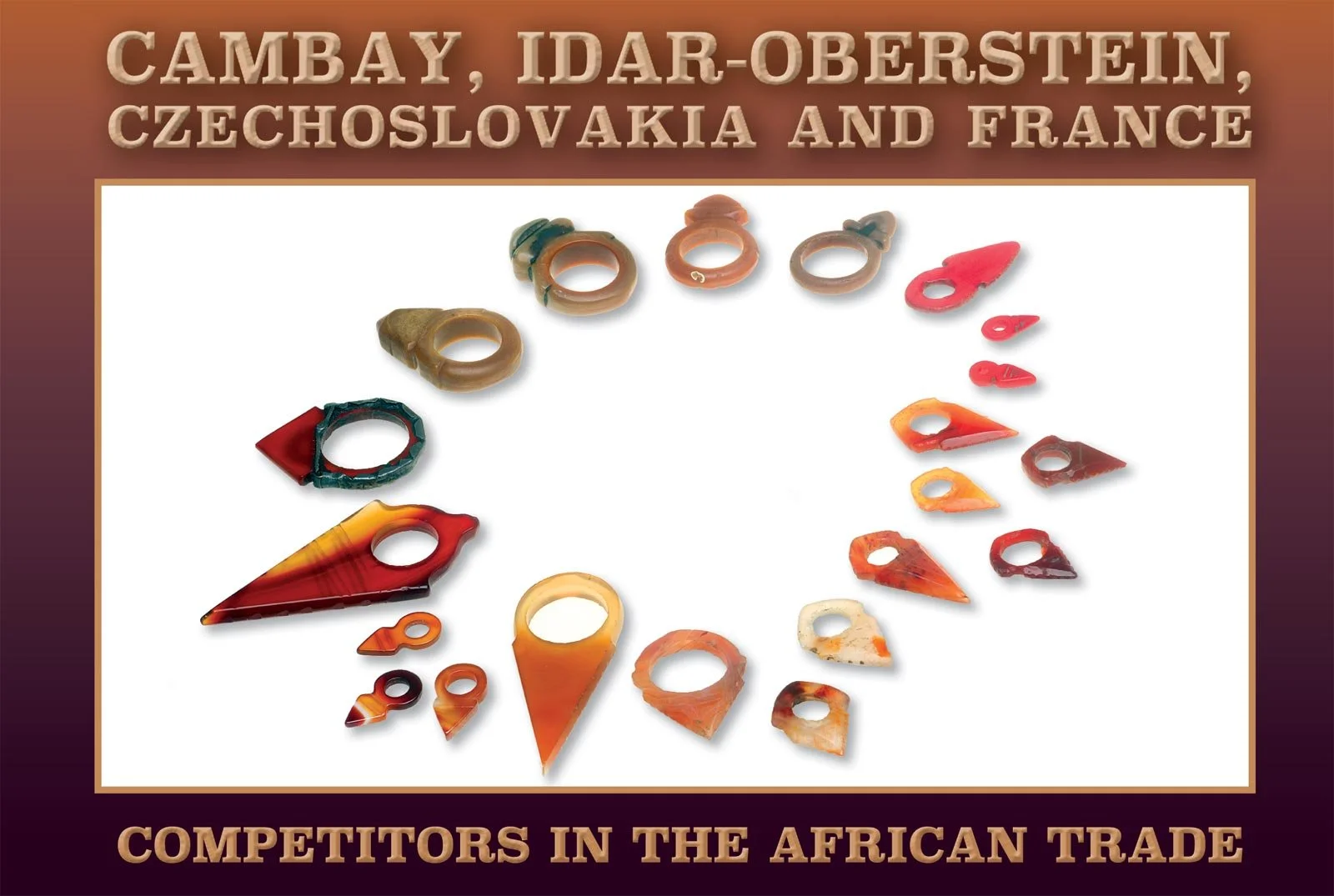

AGATE TALHAKIMT FERTILITY AMULETS FROM CAMBAY AND IDAR-OBERSTEIN, WITH CELLULOID AND GLASS AMULETS BY THE CZECH, and one homemade in Plex from Morocco. These range from 1.7 to 7.5 centimeters long. One of the celluloid amulets has been re-shaped to a more pointed shape by the user. Sourced from the U.S., Germany, Egypt and Morocco. Courtesy of the late Joel L. Malter, Dr. Peter W. Schienerl and Liza Wataghani. Photographs by Robert K. Liu/Ornament except where noted.

Recently, while photographing for Jocelyne Okrent, the daughter of the late Rita Okrent, a talented necklace designer, dealer of ethnographic beads/ornaments, and a longtime friend, she showed me new purchases of rare Cambay agate talhakimt (also spelled talhakim or called tanfouk), which I had not seen since the 1970s, and some molded glass Czech imitations of these same amulets. I had long been interested in these Indian amulets that were worn only by Tuareg women, first described by Arkell (1935a, b) as a fertility amulet, in the form of a stylized female groin and genitalia, with edge serrations as stylized pubic hair and augmented in power by its red color, and also the intense competition among Asian and European producers of beads and amulets for the African trade (Kaspers 2018, Liu 1977, 1987; Picards 1995).

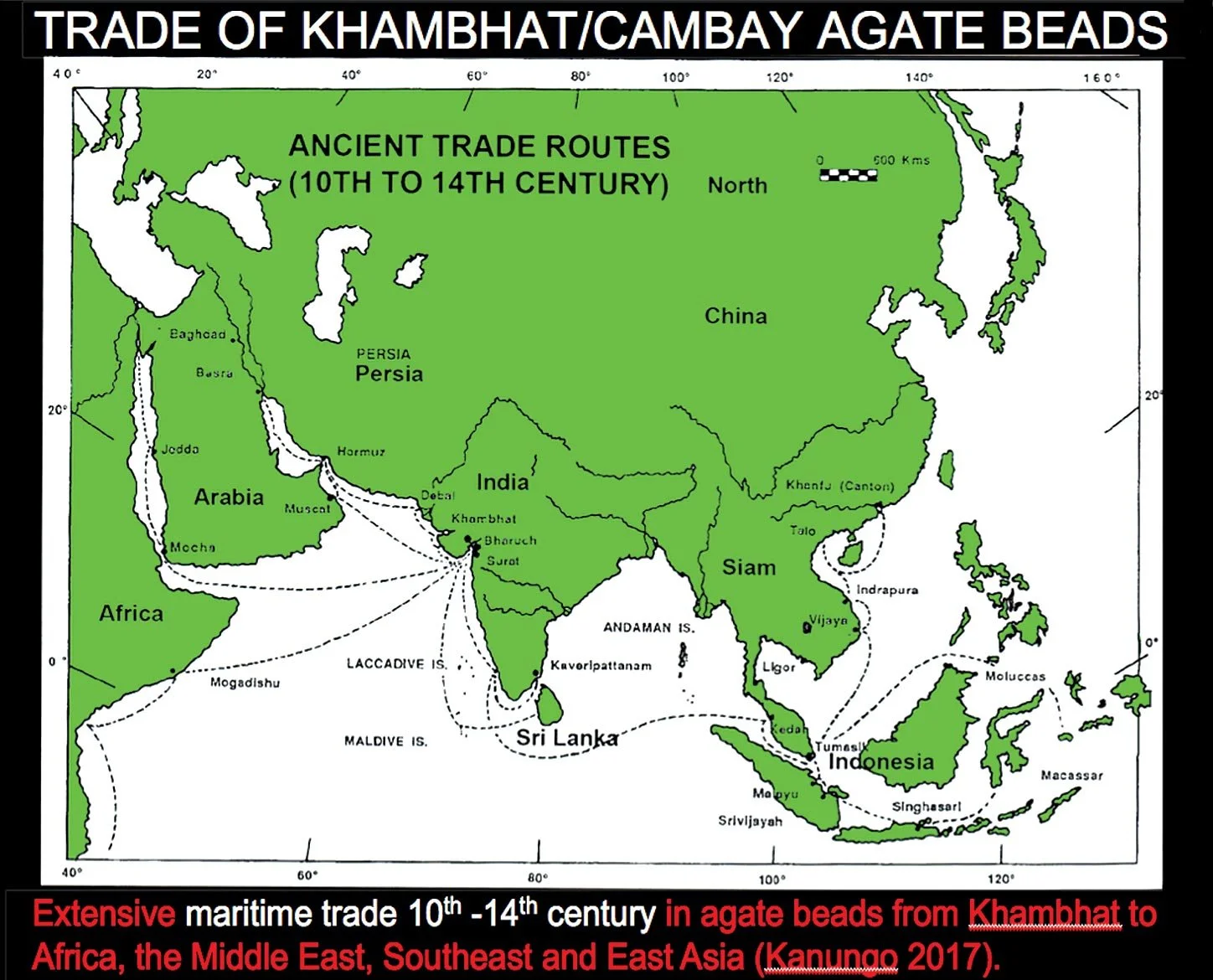

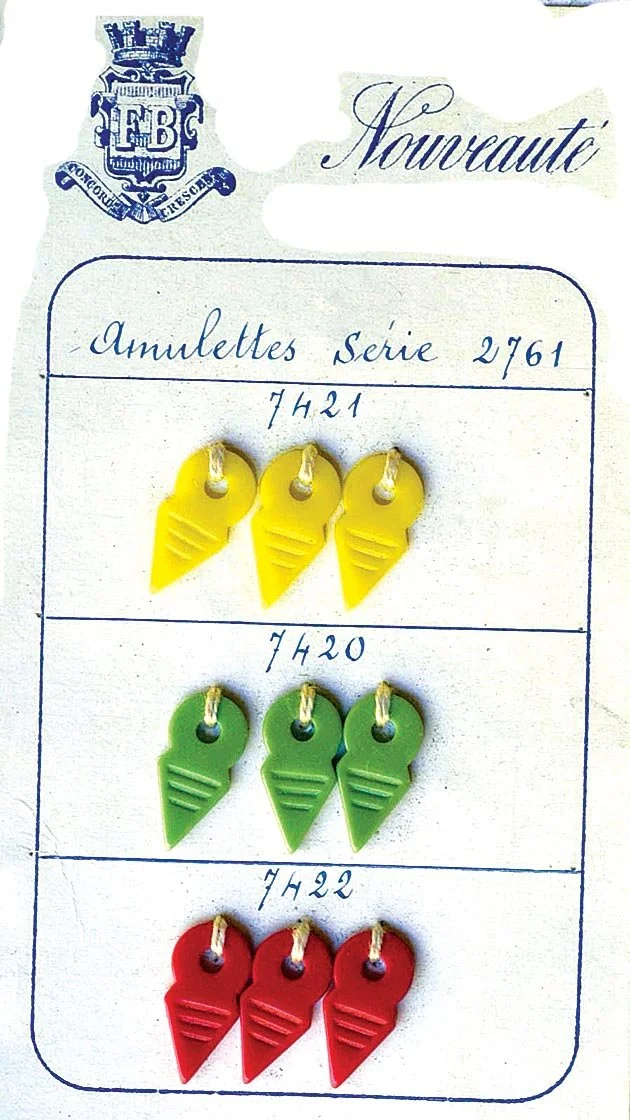

The origins for this amulet date back to ancient Indian iconography found in figurines. The agate amulets studied by Arkell had been bought by Mecca pilgrims from Indian dealers, the prototype dating to the 17th century. Both Arkell (1935a) and Milburn (1978-79) have shown Cambay and Tuareg made stone pendants that have never been seen in the recent African trade, hopefully preserved in some European museum. Some made by the Tuareg are very elaborate but shown in very small black and white photos (Milburn 1978-79: pgs. 9-11). This prompted me to look through the old literature and the Ornament Study Collection and photo archive to look for related ornaments, as well as contact Ruth and John Picard and their daughter Lauren Picard Collins of The Picard Trade Bead Museum and Art Gallery in Carmel, California, which has the largest collection of ornaments from the African Trade. They sent me images and samples of French molded glass amulets, very similar to the Czech ones, with distinct differences that I had not recognized before. The Picards had written an informative article on French Prosser beads for Ornament in 1995, describing the complexity of the various molded glass industries and their intertwined relationships.

RECENTLY PURCHASED CACHE OF CAMBAY AGATE FERTILITY TALHAKIMT AMULETS, from Burkina Faso and Niger, countries where Tuareg live. I last saw this type of Indian agate amulet in the 1970s, de-accessioned from an American museum, via the late Joel L. Malter, an antiquities dealer. I am not sure of their age, although similar ones have been dated by Arkell to 1700 (Arkell 1935a). The Cambay agate ornament industry is older, but it is not known when they started making these for the African trade. These vary in color, with at least one still in its native grey agate color, thus not heat treated, 2.4-3.9 centimeters long. A small Idar example was mixed in, at about the 5 o’clock position, showing the very deep red of the German coloring technique.

EXTREMELY RARE CAMBAY TALHAKIMT dating from 1700s, photographed at the booth of Ethnic Embellishments about 10 years ago, although I had not recognized their significance. These served as the model for all talhakimt and turm rings by the Indians, Idar-Oberstein, and other European copies of the original Indian amulets (Liu 1977: chart 1, no. 3). They are similar to turm rings or were actually considered turm rings. Note that several arerepaired, as seen by the black adhesive (?) and copper wire, as well as one repaired with a brass strip around the amulet. The repairs may reflect both their value to the Tuareg and their age. These are somewhat similar to some shown in Arkell’s 1935a article. Note the considerable variation in shapes. The differences between turm rings and talhakimt may be difficult to discern (Kaspers 2018). Courtesy of Ethnic Embellishments.

RECENT PURCHASES OF RARE CAMBAY AGATE TALHAKIMT from Burkina Faso and Niger. I have not seen this type of fertility amulets for the Tuareg since the 1970s. Using reflective and transilluminated light, one can see the large degrees of variation in the agate colors after heat treatment, due to how well the technique worked or the quality of the original agate. The light grey and dark gray examples show either a failure of the heating process or finished pieces that were not treated. Note the variation in the size of the core drilled holes, proportional to the width of the amulet. It is surprising that there would be so many core drills of slightly different diameters used. There is considerable variation in the edge serrations and horizontal lines just below the central holes. Amulets range from 2.4 to 3.9 centimeters long. Courtesy of Jocelyne Okrent.

While searching further for information or images of these amulets, I came across a photo that I had taken almost a decade ago, at a booth of Ethnic Embellishments, but did not realize its significance. This image showed the very rare Cambay agate talhakimt type from about 1700, shown in Arkell’s 1939 article, from which most of the other Cambay and European copies or derivations of the talhakimt may have been based upon (Liu 1977: Chart 1, no. 3). A number were repaired and at least one had been mounted with brass, possible signs of both their age and value to the Tuareg. These early agates are more properly considered turm rings, but having enough resemblance to talhakimt to serve as prototypes.

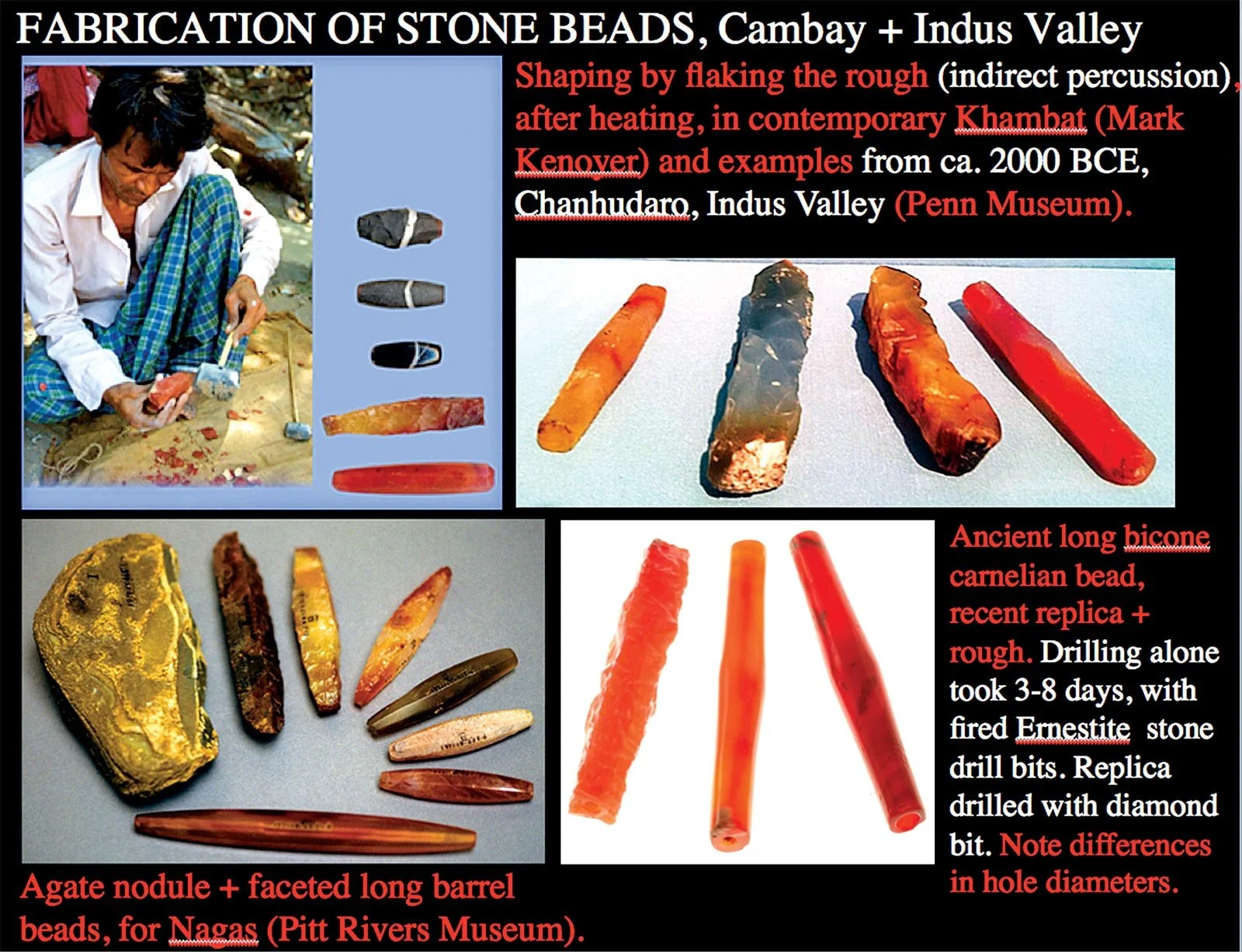

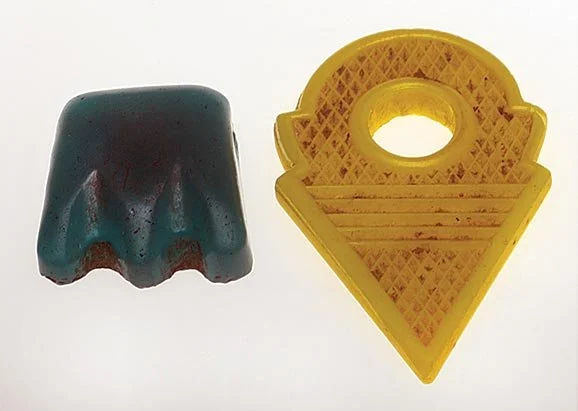

The large cache of Cambay talhakimt purchased by Jocelyne Okrent from Burkina Faso and Niger provided an opportunity to study this type of amulet, as to their manufacture and heat coloring (exposed to sunlight, followed by baking in closed earthen pot), and contrast them with examples from Idar-Oberstein. The very precise ground shapes and deep, often uniform coloring of Idar amulets may explain why Tuareg smiths almost never use Cambay agate amulets in their metal jewelry. The two images on the first and second pages of this article demonstrate the differences in crafting and coloration of the amulets favored by Tuaregs, due to technology available or not to both Indian and German lapidarists, as well as the quality of their stones and coloring techniques. In the 1800s German immigrants who went to Brazil from Idar-Oberstein found superior agates, which were exported back to their homeland (Kaspers 2018). Combined with their superior dyeing and staining techniques, Idar lapidarists were able to achieve the deep and uniform red agates, as well as colors not found in nature. While the molded glass versions of talhakimt made by the Czech and French industries are numerous in Africa, not much is known about how they are used, although Thomas Stricker told me they are worn in Mauritania as hair ornaments, strung along the temples of non-Tuareg women. Busch shows a woman with numerous tanfouk in her headdress. Arkell (1935a) does show a Tuareg woman wearing a Czech red glass talhakimt on a necklace. At this early date, the Europeans were already out competing the Indians with their carnelian and glass talhakimt, according to Arkell. Fisher (1984: 186; 193; 220-21, 223) shows a Bella woman wearing Idar talhakimt, a Mauritanian woman with miniature tanfouk by her temples and Guedra dancers in Mauritania with numerous agate tanfouk in their temple hair.

Click for Captions

“The two images on the first and second pages of this article demonstrate the differences in crafting and coloration of the amulets favored by Tuaregs, due to technology available or not to both Indian and German lapidarists, as well as the quality of their stones and coloring techniques. In the 1800s German immigrants who went to Brazil from Idar-Oberstein found superior agates, which were exported back to their homeland (Kaspers 2018). Combined with their superior dyeing and staining techniques, Idar lapidarists were able to achieve the deep and uniform red agates, as well as colors not found in nature.”

COMPARISON OF CZECH MOLDED GLASS TALHAKIMT AND CAMBAY AGATE AMULETS, showing the vast differences between how these were presented. While molded glass ones were numerous in the African trade, how they were used is not well known. The very large difference in size, shape and color demonstrates the enigma of why copies were accepted by the end users (Liu 2001). While the Cambay agates were used by Tuaregs, the glass ones are most often seen as temple dangles among Guedra dancers (Fisher 1984). The intense red of the glass copies probably enhanced their role as fertility amulets. Courtesy of Jocelyne Okrent.

COMPARISON OF CAMBAY, IDAR-OBERSTEIN, CZECH, AND FRENCH TALHAKIMT, showing large and small molded Czech and French glass examples, distinguished only by the lack of an outline rim and checkered surface of the large white glass amulet and the three horizontal lines on the miniature glass talhakimt thought to be French instead of Czech/Bohemian. The Cambay agates are recognizable by the poor core drilling and serrated edges, as well as not having only real agate colors: shades of red, sometime white. The two large agate talhakimt, one in white agate, and the adjacent turm rings, are Idar products, distinguished by precise shapes and polishing, with pre-1960 examples having more distinct features, due to polishing by grinding versus tumbling after the 1960s (Kaspers 2018, Liu 2018).

STRAND OF IDAR-OBERSTEIN AGATE BEADS, beautifully ground/faceted/polished and in deep shades of red, reasons why they were so successful in the African trade versus Cambay products. Note little distinctions like the notch on some bead edges. Faceted round beads are 2.8 centimeters diameter.

Because what I study is primarily material bought or collected via dealers in their country of origin or where they were traded, most of the data is derived from observation of the material; sometimes, there is information of where the dealers obtained their wares, and in rare cases, casual observations on how they were used. Some of these ornaments or artifacts have been written about with more detail in the relevant literature, often many decades ago. Our understanding is often by inference to related ornaments or industries, like the Cambay production of agate/carnelian beads (Arkell 1936).

CZECH VERSUS IDAR FACETED BEAD showing how badly glass wears in comparison to agate; from Mali, respectively 2.8 versus 2.5 centimeter diameters. Courtesy of Penny Diamanti, 2001.

IDAR-OBERSTEIN AGATE BEADS AND THEIR CZECH GLASS IMITATIONS; the large faceted barrel bead and the lower facetted round beads are both Czech glass imitations of Idar agates. Because glass wears more than agate, the latter are often more dull. The two slender faceted barrel beads are Idar products, traded to Africa and Sumatra.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank the late Elizabeth J. Harris, Joel L. Malter, Rita Okrent, Dr. Peter W. Schienerl and Liza Wataghani for study material and information, as well as Derek J. Content, Penny Diamanti, Ethnic Embellishments, Rita and Jocelyn Okrent, Ruth and John Picard of The Picard Trade Bead Museum in Carmel, California and Thomas Stricker for their gifts of study specimens, references, information, and photographs.

REFERENCES/BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Arkell, A. J. 1935a Some Tuareg ornaments and their connection to india. Journal Royal Anthropology Institute 65: 297-306, pl. XVII-XX.

— 1935b FORMS OF THE TALHAKIM AND THE TANAGHILIT AS ADOPTED FROM THE TUAREG BY VARIOUS WEST AFRICAN TRIBES. Journal Royal Anthropology Institute 65: 307-310, pl. XXI.

— 1936 Cambay and the Bead Trade. Antiquity 10: 292-305.

— 1939 Talhakimt and tanaghilt, some north african finger-rings, illustrating the connexion of the tuareg with ‘ankh’ of ancient egypt. man XXXIX: 184-201, pl. M.

Benesh-Liu, P.R. and R.K. Liu. 2007 Museum News: The Art of Being Tuareg. Ornament 30 (3): 70-72.

Bernasek, L. 2008 Artistry of the Everyday. Beauty and Craftsmanship in Berber Art. Peabody Museum Press, Harvard University: 125 p.

Camps-Fabrer, H. 1990 Bijoux Berbères D’Algérie. grande Kbylie-Aurès. La Calade, Édisud: 139 p.

Chakour, D. et. al. 2016 Des Trésors à Porter. Bijoux et Parures du Maghreb. Collection J.-F. et M.-L. Bouvier. Paris, Institute du monde arabe: 160 p.

Cheminée, M. 2014 Legacy. Jewelry Techniques of West Africa. Brunswick, Brynmorgen Press: 232 p.

Creyaufmüller, W. 1983 Agades cross pendants. Structural components & their modifications. Part I. Ornament 7(2): 16-21, 60-61.

— 1984 Agades cross pendants. Structural components & their modifications. Part II. Ornament 7(3): 37-39.

Fisher, A. 1984 Africa Adorned. New York, Harry N. Abrams: 304 p.

Gabus, J. 1982 Sahara. bijoux et techniques. Neuchâtel, A la Baconnièré: 508 p.

Gardi, R. 1969 African Crafts and Craftsman. New York, Van Nostrand Reinhold: 243 p.

Kalter, J. 1976 Schmuck aus Nordafrika. Stuttgart, Linden-Museum Stuttgart and Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde: 120 p.

Kaspers, F. 2018 Idar-Oberstein Agate Beads. Stones from Brazil, Cut in Germany, Sold the World Over. Ornament 40 (3): 64-67.

Kanungo, A.K. (ed) 2017 Stone Beads of South and Southeast Asia. Archeology, Ethnography and Global Connections. Gandhinagar, Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar and New Delhi, Aryan Books International: 444 p.

Leurquin, A. 2003 A World of Necklaces. Africa, Asia, Oceania, America from the Ghysels Collection. Milan, Skira, Skira Editore S.p.A.: 464 p.

Liu, R. K. 1977 T’alhakimt (Talhatana), a Tuareg Ornament: Its Origins, Derivatives, Copies and Distribution. The Bead Journal 3 (2): 18-22.

—1987 India, Idar-Oberstein and Czechoslovakia. Imitators And Competitors. Ornament 10 (4): 56-61.

—1995a Collectibles: Mauritanian Amulets and Crosses. Ornament 19(1): 28-29.

—1995b Collectible Beads. A Universal Aesthetic. Vista, Ornament, Inc.: 256 p.

—2001 DEDUCING ATTITUDES FROM ARTIFACTS. Imitations Fakes Misrepresentations Cultural Substitutes Replicas Artist Interpretations. Ornament 24 (4): 24-31.

—2002 Rings from the Sahara and Sahel. Ornament 25 (4): 86-87.

—2008 Mauritanian Conus Shell Disks. A comparison of Ancient and Ethnographic Ornaments. Ornament 32 (1): 56-59.

—2017 Ethnographic Arts: Jewelers at the International Folk Art Market. Ornament 40 (1): 62-64.

Loughran, K. and C. Becker. 2008 Desert Jewels. North African Jewelry and Photography from the Xavier Guerrand-Hermès Collection. New York, Museum for African Art: 95 p.

Milburn, M. 1978-1979 The Rape of the Agadez Cross: Problems of typology AMONG MODERN METAL AND STONE PENDANTS OF NORTHERN NIGER. Almogaren IX-X: 135-154.

Schienerl, P.W. 1986 The Twofold Roots of Tuareg Charm-cases. Ornament 9(4): 54-57.

Seligmann, S. 1927 Die magischen Heil- und Schutzmittel aus der unbelebten Natur mit besonderer Berueksichtigung der Mittel gegen den Boesen blick - Eine Geschichte des Amulettwesens. Stuttgart: 193-195.

Van Cutsem, A. 2000 A World of Rings. Africa, Asia, America. Milan, Skira: 230 p.

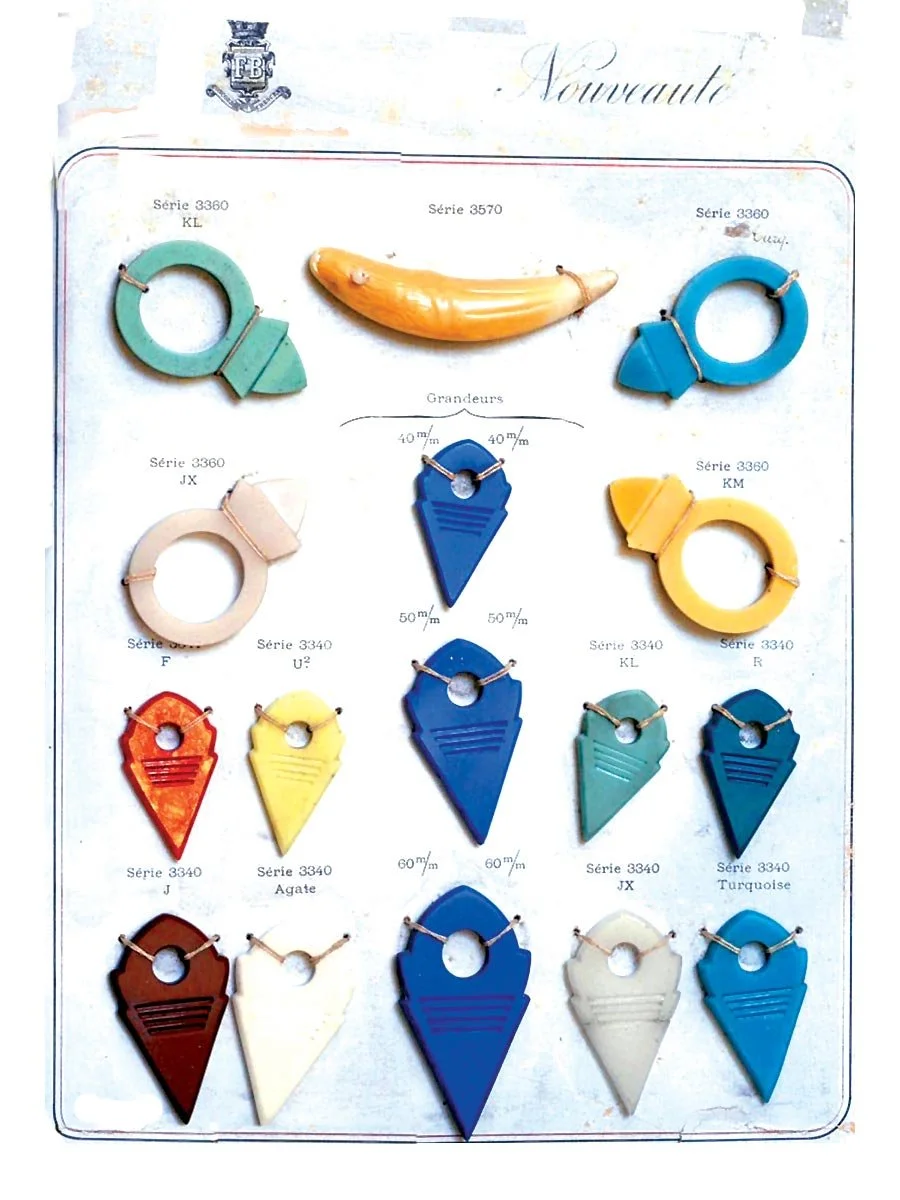

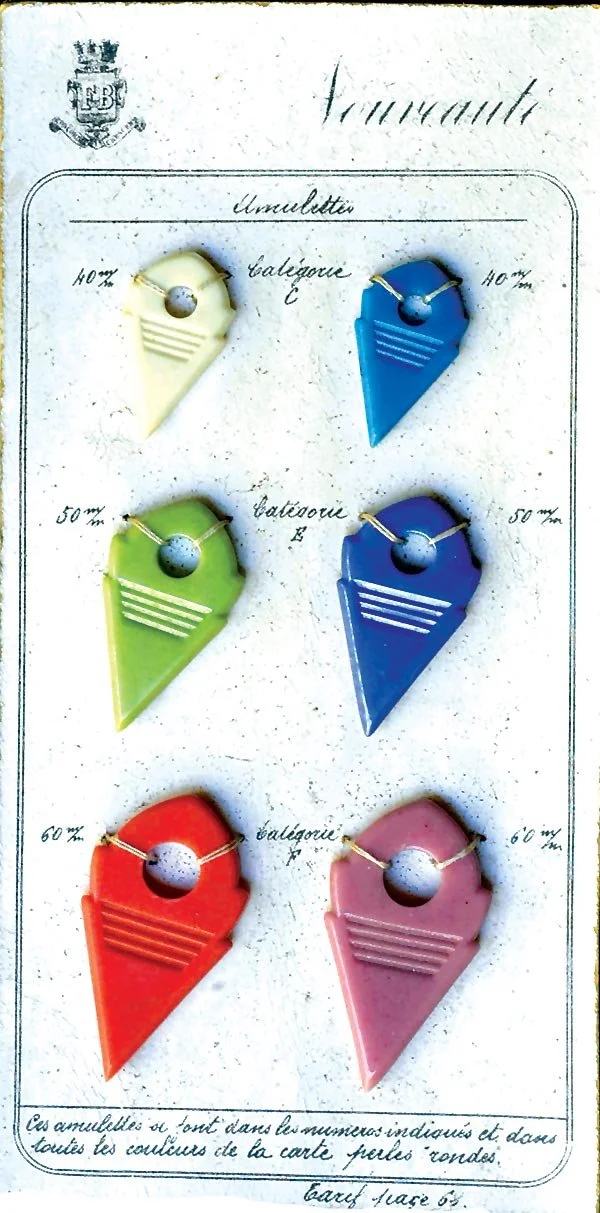

FRENCH PROSSER MOLDED GLASS TALHAKIMT, TURM RINGS AND IMITATION LION’S TOOTH in various sizes, colors, some rarely seen in the African trade and much less numerous than Czech molded glass. All the French glass examples more closely follow agate prototypes, as they are more simple than Czech examples, except for color. The glass lion’s tooth is painted in near natural colors. All French Prosser sample cards courtesy of Ruth and John Picard.

CZECH MOLDED GLASS TALHAKIMT versus unidentified amulet, perhaps stylized claw; lower image of Czech versus French talhakimt, with the translucent blue one much simpler and closer to agate examples. Above examples from Rita Okrent and the Picards.

A LARGE NUMBER OF CZECH MOLDED GLASS TALHAKIMT, ARRANGED BY COLOR, showing the variation in the glass colors, which are usually uniform. The blues demonstrate the largest variation. Despite this large collection, there does not appear to be more than seven primary colors used, with transparent ones rare. Being molded, one would expect they would be very uniform in size, but a sample measured 5.5, 5.35 and 5.15 centimeters long; possibly due to differential shrinkage when fired. Photograph courtesy of Thomas Stricker.

Images on left: IDAR-OBERSTEIN TALHAKIMT WITH TWO HOLES, image downloaded from Internet. Right-hand image of similar Idar talhakimt, mounted elaborately by a Tuareg smith; until I recently saw these two hole talhakimt on the Net, I thought that Tuareg jewelers drilled the second hole. Note the precise metalwork done by the Tuareg smith, showing they are the best jewelers in Africa. Right-hand photo by Robert K. Liu/Ornament. Images on right: RARE TUAREG NECKLACE STRUNG ON HUMAN HAIR, using carved cowrie disks, Idar-Oberstein sourced talhatana mounted with brass, some barely visible green dyed Idar amulets, Idar dyed agate drop pendants, Mauritanian brass beads, unidentified red beads, copal imitation, and an Engina shell. Courtesy of the late Elizabeth J. Harris. TUAREG TADNIT NECKLACES worn by adult women, strung with long silver cylindrical beads, ellipsoid glass beads, small triangular agate and silver pendants, small black and blue beads, and large Idar talhakimt, two silver Tuareg tanaghilt or Tuareg crosses, and a large silver diamond-shaped silver pendant with dangles, almost identical to necklaces shown in Arkell, as well as different types of necklaces worn by Tuareg women of various social classes in Darfur, Sudan (1935a), sketched in Liu (1977). This photograph was taken many decades ago in a British museum, possibly by Sue Heaser.

VERY RARE TUAREG WOMAN’S HEAD DRESS possibly strung on hair, decorated withlarge numbers of Idar-Oberstein banded agate talhakimt and cast Tuareg silver ornaments. The long strip on the left has what may be three agate turm rings. The large numbers of agate amulets used on each head dress may account for the large numbers of such agates being in the African trade. Photograph courtesy of Thomas Stricker.

COMPARISON OF CZECH, FRENCH, IDAR, AND CAMBAY TALHAKIMT in molded glass and agate. Note that the two blue and white French molded glass versions on the bottom row are much closer to the Cambay prototype, except for size and color. The molded glass amulets are used in Mauritania as hair ornaments, dangling from the temples of non-Tuareg women, according to Thomas Stricker. Guedra dancers also wear talhakimt in their hair (Liu 1995). The puzzle is why these very different and colorful amulets are accepted, like so many imitations that are so easily differentiated from the prototype. Courtesy of Jocelyne Okrent, Ruth and John Picard, and Thomas Stricker.

Robert K. Liu is Coeditor of Ornament, for many years its in-house photographer, as well as covering ethnographic and ancient jewelry, and events related to wearable art, both in and out of the Ornament studio. 2026 marks the fifty-second year of Ornament Magazine, which he and his late wife Carolyn Benesh began in 1974. Not always conscious of what was central to his interest in personal adornment, in recent years he has realized that the driving force behind his research and writing has really been the evolution and comparison of human skills, whether expressed in ancient, ethnographic, or contemporary jewelry, or in scale models and mechanical vehicles, and how they are made and operate. A lifetime avocation of scale modelmaking culminated in the publication in 2021 of a book on naval ship models of World War II, published in the United Kingdom. He plans to soon write another book in this field. Chinese and other faience, composites, and glass, whether ancient, ethnographic or contemporary are among some of his research interests, as well as vintage Chinese folk jewelry. In this issue, he writes about the Tuareg agate fertility amulet, the talhakimt. First made in numbers in India for the African trade, this was then produced in an improved and precise version by the Germans of Idar-Oberstein, who used a better agate from Brazil, as well as celluloid examples. Due to the lucrative market for ornaments in the African trade, the Czech, French and others produced molded glass copies of this amulet in sizes and colors never made in agate. In Traditions + Innovations, Liu writes about Tuareg and North African pendants based on the protective symbolism of five, or the hamsa, both expressed in a very different manner.