Deb Karash Volume 43.2

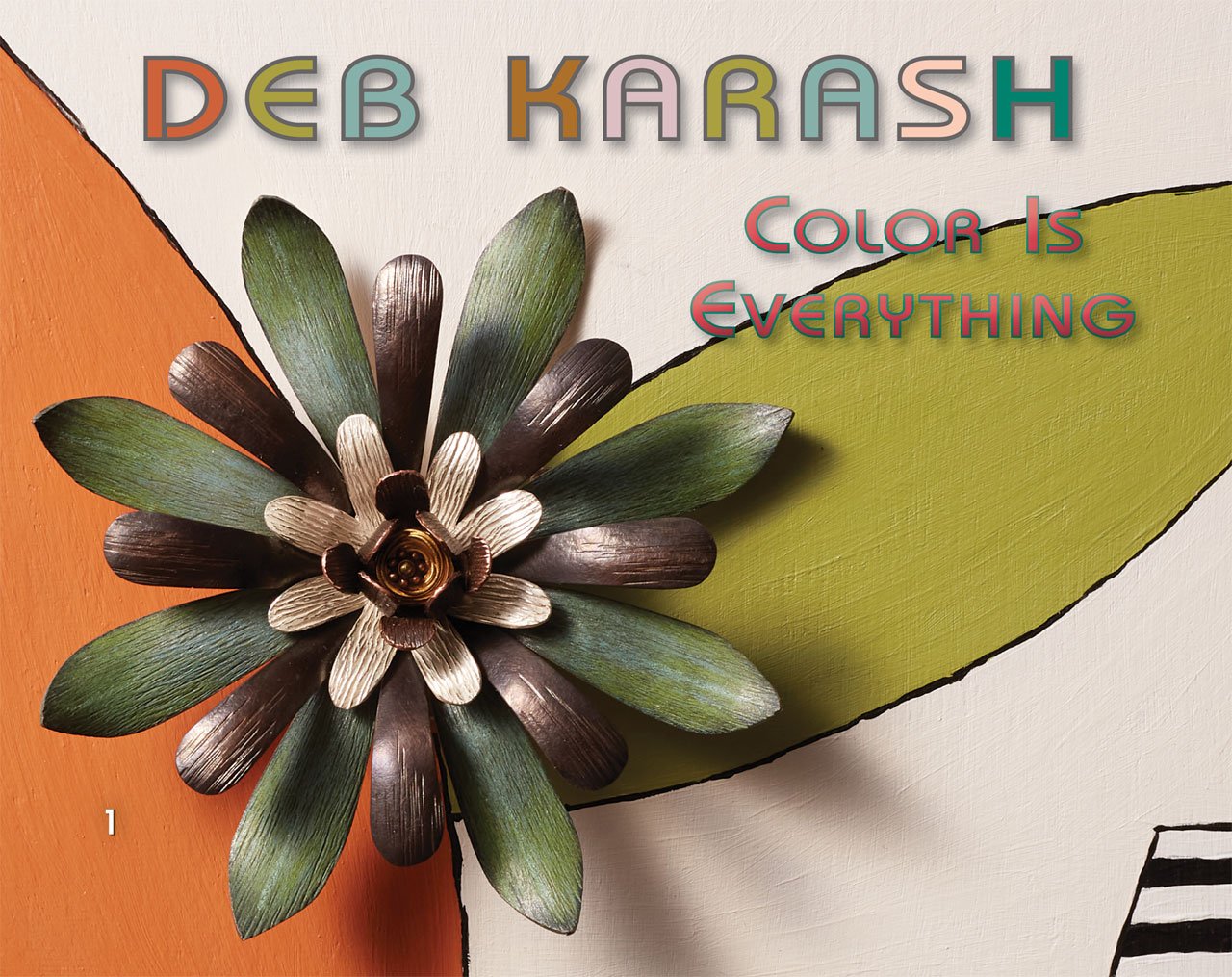

UNTITLED of acrylic paint, sterling silver, copper, twenty-four karat gold, Prismacolor pencil drawing on copper; 20.3 x 20.3 x 3.8 centimeters gallery panel with 8.9 x 8.9 x 2.5 centimeters brooch, 2022. Photographs by XO Crew.

DEB KARASH.

After five decades in the flat plains of the Midwest, jewelry artist Deb Karash found “the studio of her dreams” in the mountains of Western North Carolina. Located in an old schoolhouse on a wooded island in the middle of the French Broad River, it offered plenty of space with big windows looking out over the rippling water. So, in 2007, she moved from the fifth-most populous city in Illinois, Rockford, to the “charming little, teeny, tiny town” of Marshall, where residents had to (and did) make their own fun. She had reached a transitional point in her life, and the instant community and camaraderie of the Marshall High Studios (recently renovated by Rob Pulleyn, founder of Lark Books), were a welcome change. Now she lives with her partner, artist and gallerist David Trophia, in nearby Asheville, and embraces its music, food, weather, walkability, and thriving arts scene. A new solo exhibition of her colorful brooches at Wesleyan College in Macon, Georgia, reflects Karash’s inventiveness and joie de vivre that are fostered by this delightful setting.

Art, jewelry and craft were always present for Karash as a child. Her father’s hobbies included woodworking, stained glass and model airplanes, while her mother sewed, knitted, crocheted, and dealt in antiques. Karash went to antiques auctions and craft shows with her mother and began collecting metal thimbles and vintage jewelry at a young age. She also enjoyed sewing, embroidery, and, in the 1970s, macramé. She took a lot of art classes in college, but got an associate degree in economics, expecting to become a home economics teacher. It was not until her late thirties that Karash took her first jewelry making class, offered by an artist she met at a local fair who taught in her home. “I was hooked.” She went back to school and finished her Bachelor’s degree as well as her Master of Arts degree in jewelry at Northern Illinois University. Though focusing on jewelry and metalwork, she turned most often to her fiber teacher, Renie Breskin Adams, for critiques because she appreciated Adams’ honest feedback and expertise as a colorist.

Karash’s early jewelry involved mixed metals, totem forms and some stones. Intrigued by the jewel hues and color variations of the Chinese Turquoise, sugilite and agates she used, she began to consider ways to bring their tonal shifts to her metal. She quickly dismissed the obvious method—enameling—because she disliked the process. Then she worked with chemical patinas, but they did not offer the level of control she wanted. Eventually she turned tothe colored pencils scattered around her studio, recognizing that they had the vibrancy, immediacy and flexibility that she desired. At the time (the late 1990s), she knew that Helen Shirk in California was using colored pencils with her large metal vessels, though Karash, who was still early in her career as a jeweler, was hesitant to ask the more experienced artist about her process. Likewise, she demurred from approaching Marilyn da Silva, who also uses colored pencils with metal. Instead, she spent more than a year developing her own approach through trial and error. She marvels now that each of them uses a different technique.

UNTITLED of acrylic paint, sterling silver, copper, plastic/graphite casting from nature, glass beads, Prismacolor pencil drawing on copper, 20.3 x 20.3 x 3.8 centimeters gallery panel with 9.5 x 9.5 x 2.5 centimeters brooch, 2022. UNTITLED of acrylic paint, sterling silver, copper, Prismacolor pencil drawing on copper, 20.3 x 20.3 x 3.8 centimeters gallery panel with 14.6 x 6.4 x 0.6 centimeters brooch, 2022.

UNTITLED of acrylic paint, sterling silver, copper, twenty-four karat gold, Prismacolor pencil drawing on copper, 20.3 x 20.3 x 3.8 centimeters gallery panel with 14.0 x 7.6 x 0.6 centimeters brooch, 2022.

In addition to color, Karash loves volume and texture, and achieving all three in individual works has involved experimentation, custom materials and product development. She does all of her color work on copper, but she wanted the metal next to the wearer’s skin to be silver. The silver layer on readily available sheets of bimetal (made of two layers of metal, in Karash’s case, silver and copper) was too thin for her to be able to texture like she wanted, so she worked with a bimetal maker to get a thicker layer of silver. She applies a chemical patina to the copper to give it tooth—a rough surface to hold the color—describing this step as “twitchy” and subject to shifting weather conditions. Once the copper is ready, she uses Prismacolor pencils to draw directly on the metal, slowly and carefully shading with different pencils and blending with toothbrushes. She burnishes the layer of color, sprays it with a fixative, and repeats the coloring and spraying steps once more. She completes the now saturated surface with a coat of wax polish, giving it a satiny finish. Most of her works feature multiple parts, and because of the various metals and delicate colored surfaces, she rivets those pieces together. Riveting within her voluminous forms, though, presented challenges as well.

To solve this issue, Karash drew upon inspiration from educator and author Tim McCreight (with whom she took a workshop) and decided to make her own tools. She wanted to be able to rivet deep inside of a three-dimensional shape, so she made an elongated steel cone that could support the work without damaging its surface. Then she needed something to hold the cone, desired a non-marring surface, and thought that it should be small and easily portable. One step led to another, and she eventually developed her Little Black Block. It measures about 3” x 4” x 1”, and is made of Delrin®, a dense thermoplastic manufactured by DuPont. It also has dapping depressions, rolled edges, a V-groove, swage spots, and a flat surface on the bottom—and jewelers can easily alter the block as needed. She has sold hundreds of these compact, multifunctional tools since she introduced them in 2018, and in 2021, Rio Grande began carrying them. (She wishes that her grandfather, a tool and die maker, could have seen this accomplishment.) The Little Black Block and a collection of hammer handpieces (like miniature precision jackhammers)—a life-changing tool suggestion from Seattle jeweler Andy Cooperman—allow Karash to create the work she envisions.

UNTITLED of acrylic paint, sterling silver, copper, vintage stamens, Prismacolor pencil drawing on copper, 20.3 x 20.3 x 3.8 centimeters gallery panel with 16.5 x 7.6 x 1.3 centimeters brooch, 2022. UNTITLED of acrylic paint, sterling silver, copper, twenty-four karat gold leaf, Prismacolor pencil drawing on copper; 20.3 x 20.3 x 3.8 centimeters gallery panel with 3 brooches, 5.7 x 5.7 x 1.3 centimeter brooches, 2022. UNTITLED of acrylic paint, sterling silver, copper; 20.3 x 20.3 x 3.8 centimeters gallery panel with 20.3 x 6.4 x 1.3 centimeters brooch, 2022.

When asked about the imagery she uses, which is mostly botanicals, insects and birds, geometrics, and a few robots and rockets, she replies, “In my work the consistency is more process than imagery,” and “flowers were just a shape to take the color.” So, for Karash, color comes first. She emphasizes, “Well, color is everything,” adding, “most of us have a favorite color. Color is documented to have an effect on everything from our emotions to our appetite. Every color offers unending nuance. Light, dark, crisp, dusty.” She often draws inspiration from vintage textiles and wallpapers and describes her style as “kind of cartoony.” In recent years she especially has enjoyed making work inspired by “the rabbit hole of imagery” around steampunk culture. One of her collectors is a steampunk devotee with “an amazing array of costumes,” who has developed a character who captains an airship; he asked Karash to create a brooch for him about his airship and one featuring his character’s logo. She also, just for fun, made a Steampunk fish during a workshop, which he acquired as well.

With her recent body of work for the exhibition at Wesleyan, Karash presents each brooch on a small painted canvas. Though she collaborated once in the past with another artist who made drawings that Karash colored and paired with brooches, this is the first time that she has created paintings as part of her jewelry work. Karash considered most of these in pairs or small groupings, using complementary lines and colors. The flat tones of the canvases draw attention to the shaded details of the jewelry, and the shadows from the brooches add another layer of interest to the paintings. She prefers seeing her work on a wall (or body) to seeing it in a case and enjoyed creating the environments for these new works. The brooches easily can be removed from the paintings and worn.

Karash’s consideration of presentation likely reflects her earlier career as a department store display designer back in Illinois. That experience certainly influenced her when she participated in craft shows. She explains that she often went a little overboard—which won her several “best booth” awards—considering not only how the jewelry would look as visitors approached it, but how it would look when they tried it on; she made sure they had a place to hang their purses and that they would be well lighted when looking in the mirror.

The Wesleyan exhibition features numerous flower brooches, one with bright silver, soft copper and a layer of petals with delicately shaded blues and greens [1], and another with narrow spiky petals of pinks and oranges, with beads for added texture, and a form in the center cast from the middle of an actual flower. [5] One, a pale yellow flower with hints of orange and a long stem, has stamens “just like the ones in the old-style artificial flowers that she used for making wreaths for her mother’s door.” [8] A pair that particularly stands out is much lighter in feel than the others, with gently bending stems and a few simple leaves. [9 & 10] The flowers are lively and colorful, each with a unique combination of forms, hues and textures.

UNTITLED of acrylic paint, sterling silver, copper, twenty-four karat gold leaf, Prismacolor pencil drawing on copper, 20.3 x 20.3 x 3.8 centimeters gallery panel with 11.6 x 7.6 x 1.9 centimeters brooch, 2022.

Karash also created several brooches with abstract designs, some with retro modern curves, others with strong geometric forms. A brooch of vibrant blues, greens and oranges has folds that suggest drapery or water, with its shiny brass rivets appearing like upholstery buttons or glimmering stones on a streambed. With several she curls or folds the textured silver to the front. In one, brilliant colors peek out of open conical forms—she professes an admiration for cone shapes. [3] Surprisingly, one of her favorite brooches does not have added color—she preserved the natural copper in a trio of flat organic rings—but she enjoys that its two pins (one on each end) allow the wearer to play with how it is worn on the body. [7]

Karash believes in the power of jewelry, stating, “Jewelry is about intimacy and connection. It has a history of marking special moments in time and it is one of the rare art forms that we carry out in the world with us. We use it to tell the outside world something about ourselves.” One of the strengths of her jewelry is that it can spark conversation. The surfaces she creates are unusual—the copper is completely covered by pencil, so viewers often wonder what the materials are and ask about this curious visual effect. She hopes that people use some of her jewelry to commemorate special occasions and that it continues to create positive experiences and connections as people wear it out in the world.

After many years focusing on her studio work and craft shows, Karash now devotes much of her time to leading workshops—about eight a year. She explains, “I’m a big proponent of the workshop system. I think if you have a little bit of skill and you know what you want to do, you should just take workshops.” She took many workshops herself, experiencing their benefits firsthand, and sees them as a worthwhile alternative to MFA programs, especially as the costs of college and graduate school skyrocket. “If you actually want to be a working artist, it’s going to take you forever to pay off those college loans.” She explains that in a concentrated workshop, students can learn as much as in a semester-long class. Karash also truly enjoys sharing her love of color and the techniques she’s developed (while, of course, encouraging students to find their own styles), as well as helping students advance their skills and approaches. It was leading workshops at Penland and Arrowmont that introduced her to the part of the country where she now lives.

Deb Karash modestly describes her superpower as, “I can make pretty.” While she certainly excels at that, she can also develop tools and successfully change careers, and build a reputation as a studio jeweler and teacher that brings scores of students to her each year. She is resilient, weathering a divorce and ovarian cancer, and adaptable, learning how to teach online during the pandemic. Her approach to life is, “If I can do it myself, I should,” and that led her to invent a distinctive approach to color and metal. She continues to find ways to introduce variety to her jewelry practice and is considering incorporating fabric in future pieces. The exhibition at Wesleyan provides viewers a chance to join in her creative celebration of color.

UNTITLED of acrylic paint, sterling silver, copper, vintage stamens, Prismacolor pencil drawing on copper; 20.3 x 20.3 x 3.8 centimeters gallery panel with 9.5 x 7.6 x 3.2 centimeters brooch, 2022.

Ashley Callahan is an independent scholar and curator in Athens, Georgia, with a specialty in modern and contemporary American decorative arts. She enjoys every opportunity to learn about, talk about and write about contemporary jewelry. She found Deb Karash’s technique and dedication to color intriguing. Callahan also appreciates the draw of the beautiful landscape in Western North Carolina, especially as the fall colors emerge. Callahan has an undergraduate degree from Sewanee and a master’s degree in the history of American decorative arts from the Smithsonian and Parsons. The University of Georgia Press recently published her book Frankie Welch’s Americana: Fashion, Scarves, and Politics. She is also the author of Southern Tufts: The Regional Origins and National Craze for Chenille Fashion (UGA Press, 2015) and co-author of Crafting History: Textiles, Metals, and Ceramics at the University of Georgia (Georgia Museum of Art, 2018). The former two books touch on threads previously covered in Ornament Volumes 35, No. 1 and 39, No. 3.