Sporting Fashion Volume 43.1

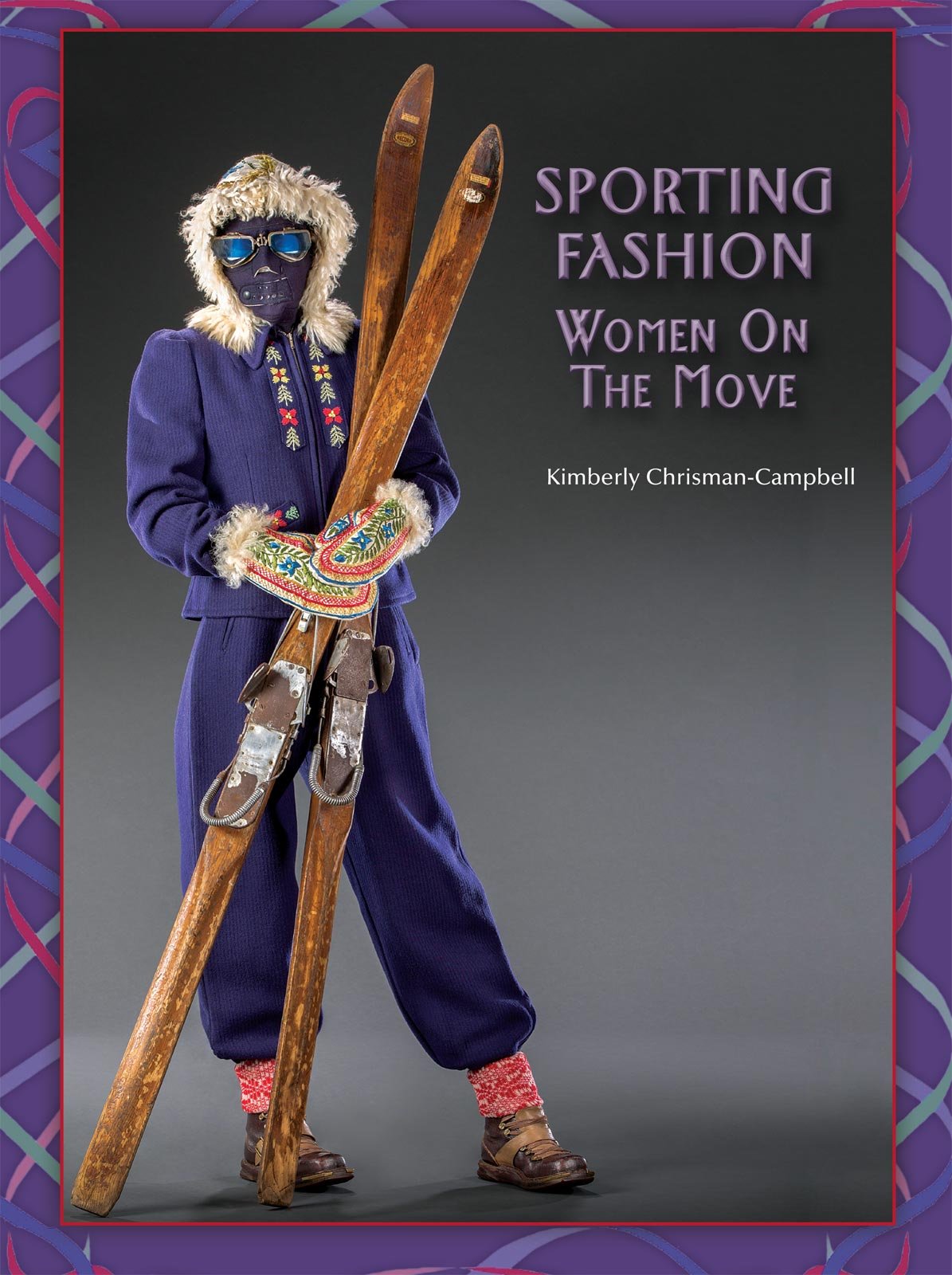

SKIING ENSEMBLE, 1930s: SKI SUIT of embroidered boiled wool and wool knit, ca. 1935–40. HOOD AND MITTENS of rayon embroidered suede and fur, Europe, ca. 1925–50. SKI MASK of wool felt, ca. 1940. GOGGLES by F.O.P.A.I.S. [Fabbrica Occhiali Per Aviazione Industrie Sports] of metal, glass, plastic, rubber, and elastic, Milan, Italy, ca. 1930-40. SOCKS of wool knit, ca. 1925-40. SKI BOOTS with label: Prast 109 of leather, metal and rubber, ca. 1930–40. SKIS by C. A. Lund Company of hickory and metal, Hastings, Minnesota, ca. 1940. All photographs © FIDM Museum. Photographs courtesy of FIDM Museum & AFA.

TENNIS ENSEMBLE, 1910s: DAY ENSEMBLE of cotton and cotton crochet, United States, ca. 1914. HAT by McDermott-Wilser Company of silk crepe, straw and silk ribbon, Minneapolis, Minnesota, ca. 1913-17. RACQUET COVER of cotton and mother-of-pearl button, United States, ca. 1900–1915. BOOTS of cotton canvas, leather and composite/metal buttons, United States, ca. 1910-15. NECKERCHIEF AND BELT, props.

With the unusual spectacle of back-to-back Olympic Games fresh in our collective memory, the touring exhibition “Sporting Fashion: Outdoor Girls, 1800-1960” is a timely look at women’s sportswear and outdoor gear for all seasons. Organized by the Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising Museum in Los Angeles, California, it features extraordinary (and extraordinarily rare) objects, including specialized underwear, accessories and footwear worn by adventurers, athletes and spectators. An accompanying catalog, which has received the Costume Society of America’s Millia Davenport Publication Award, has a foreword by famed sportswoman and style icon Serena Williams—underscoring the modernity and feminist appeal of this centuries-spanning show.

In ancient times, organized sports doubled as military training, and they were performed in the nude—meaning that women were excluded. Riding and hunting were among the first sports open to women, who wore skirted versions of menswear. Other forms of physical activity made surprisingly early appearances. In the eighteenth century, women participated in cricket and boxing; croquet and archery followed.

The show picks up at the dawn of the nineteenth century, as women began to enjoy new forms of physical exercise in clothing designed to facilitate movement and shield them from the elements. Women increasingly visited public beaches, pools and seaside resorts, where “bathing” was considered not only healthy but fashionable. (“Bathing” meant getting wet, usually with the help of a female “dipper”; actual “swimming” would come later.) Empress Eugénie built a beach villa in Biarritz in 1855. By the end of the 1800s, the “girl athlete,” as Harper’s Bazaar called her, was no longer an unnatural oddity but an admired archetype, thanks in part to the flattering sketches of Charles Dana Gibson and the widespread popularity of the bicycle.

Tennis was one of the first sports open to both men and women, and still hews to its early fashion traditions, such as wearing white and skirts. Williams, in her introduction, recounts the controversy over her Black Panther-inspired French Open catsuit—a compression garment designed to promote blood circulation after childbirth that remains a rare instance of pants worn by a woman on the court. Indeed, the show demonstrates that women could do just about anything in a skirt: horseback riding, biking, fencing, roller skating, mountaineering. It wasn’t until 1912 that Vogue noted that breeches were becoming usual for riding; shorts, skorts and other two-legged forms of sportswear gradually followed, offering unprecedented glimpses of limbs and skin.

RIDING ENSEMBLE, 1910s: RIDING HABIT by P. N. Degerberg of wool twill, brushed wool and suede, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1912. RIDING HAT by Henry Heath Limited of silk plush, silk grosgrain ribbon, silk taffeta ribbon, and silk net, London, Great Britain, ca. 1908–12. RIDING STOCK by Stern Brothers of silk grosgrain, New York City, ca. 1900–1915. RIDING WHIP of leather, metal and waxed cord, Europe or United States, ca. 1900–1910. RIDING AWARD by Boston Regalia Company of silk satin ribbon and metal; associated with the Morristown Field Club, Boston, Massachusetts, 1912. RIDING BOOTS of leather, Europe or United States, ca. 1900–1915. GLOVES AND FLOWER, props.

As horses, yachts, carriages, bicycles, and motor vehicles made the transition from everyday transportation to sport, women’s clothing evolved to optimize safety and performance. Vogue launched a “Motor Notes” column to chronicle the latest developments in automotive technology and dress. The Outing Magazine had once linked proper dress to equestrian technique: “If she looks right, she probably rides well.” Similarly, Vogue credited “the new motor coats” with popularizing the sport of motoring rather than the other way around. “Car clothes” of the 1950s updated the duster and veil of the turn of the century with scarves and sunglasses for convertibles and slim trousers for navigating bucket seats. Bicycles and Vespa scooters promoted “pedal pushers” and capri pants—including a kicky Pucci patterned pantsuit in the show, paired with a helmet modeled after a straw hat.

Long before the advent of athleisure, sportswear and streetwear influenced each other; both could be functional as well as stylish. Fashion is uniquely conducive to self-expression and personal branding, which are increasingly part of sports. The show blends heritage sportswear brands like Keds, Pendleton, Stetson, Spalding, Jantzen, and Abercrombie & Fitch (founded in 1892 as a purveyor of outdoor goods) with high-end couturiers like Coco Chanel, Cristobál Balenciaga, Jean Patou (whose brother-in-law was a professional tennis player), Emilio Pucci (a member of Italy’s Olympic ski team), and André Courreges (an avid Basque pelota player). Lest you confuse them with street clothes, though, many of the garments have appropriately athletic iconography. Yachting and bathing clothes featured nautical imagery like anchors, ship’s wheels and seahorses. Riding garb was blazoned with pictures of horses, and game bags were embroidered with fox heads. Jantzen’s iconic diver logo is still in use today.

The show is not only a three-dimensional social history but a tribute to innovative textile and fashion design. In 1871, Harper’s Bazaar advised that ladies’ traveling ensembles should “shed dust” and “must be made of a fabric that will not rumple easily... or cockle from dampness.” Shooting ensembles had built-in pads at the side of the waist where a rifle could rest. Cycling, climbing and riding ensembles might convert from pants to skirts and back using clever panels fastened by buttons; breakaway “safety skirts” would not catch on the saddle horn if the rider was thrown. In other cases, lead weights anchored hemlines in place; hidden pockets kept cash, balls and other essentials safe. Before Spandex and Lycra, swimsuits, gymsuits and other body-conscious sporting garments got their stretch from knitted wool. Bulbous leg-of-mutton sleeves may look like an odd choice for exercise, but they allowed a range of motion that fashionable fitted sleeves did not. Similarly pneumatic collapsible calash bonnets protected the head without crushing the hair. Sportswear designers sought out unconventional materials that could withstand saltwater or rainwater—including rarities like an 1860s rubber rain mantle and a linen-and-loofah beach bonnet. (If some of the swimsuits in the show look like they wouldn’t survive in the water, it’s because they were worn poolside or beachside, and never intended to get wet.)

In many cases, athletes and adventurers became innovators by default, as there was nothing on the market suitable for them to wear. Amelia Earhart, Suzanne Lenglen, Alice Marble, and Helen Jacobs all launched fashion labels. Explorer Lillian Burnham, a travel correspondent for Vogue in the ‘teens, adapted boy’s clothes—including baggy trousers—to her needs. Indeed, the woman athlete has, historically, been the harbinger of modernity, pushing social and sartorial boundaries. Many of the ensembles in the show were so far ahead of their time that they could still be worn today; others—like a steampunk-ish motorcycle belt equipped with reflectors—look downright futuristic. Sports gear continues to forecast new fashion trends and technology; if you want to know what we’ll all be wearing in ten years, look at athletes.

Click for Captions

“The show is not only a three-dimensional social history but a tribute to innovative textile and fashion design. In 1871, Harper’s Bazaar advised that ladies’ traveling ensembles should “shed dust” and “must be made of a fabric that will not rumple easily... or cockle from dampness.””

The exhibition was years in the making—not only because of the challenging logistics of organizing a touring exhibition and preparing an illustrated catalog, but because of the time-consuming process of collecting hundreds of garments and accessories and historically appropriate props. The curators went to great lengths to track down rare pieces, many of which bear evidence of athletic wear and tear. One of their most exciting finds in the show is a Yale sweater worn by a cheerleader, emblazoned with a Y. “We specifically needed an example from the 19-aughts and wanted a turtleneck,” says co-curator Kevin Jones. “They are almost non-existent. So, we had an advertisement created for the Yale Alumni newsletter hoping someone would see it and contact us. Success!”

Click for Captions

BASKETBALL ENSEMBLE, 1910s: BASKETBALL UNIFORM of cotton sateen, linen and cotton, Brenham, Texas, 1919. Gift of Steven Porterfield. SPORT BOOTS of cotton and suede, United States, ca. 1910–20. BASKETBALL of suede leather, United States, ca. 1915. STOCKINGS, prop.

Sixty-five fully-outfitted mannequins highlight the complexity of dressing for physical activity and the elements, with specific headgear, eyewear, gloves, shoes, and other accessories. In many cases, the mannequins are frozen in motion, perched on sleds, bicycles or stacks of suitcases, or wielding barbells, fencing foils or cricket bats. An ice skater seems caught mid-spin. “From the beginning of the project, we wanted a sense of bodily movement,” Jones says. “We wanted to see how far we could take the movement by positioning the mannequins in ways that echoed period illustrations, such as the 1810s ice-skater who had fallen, but would still be safe for the dressed objects. Sometimes body parts had to be carved from Ethafoam because of arm or leg placement and weight.”

The show covers water sports, winter sports, equestrian sports, ball games, motor sports—more than forty athletic activities, though these are broadly defined. Ballooning, walking, train travel, picnicking, and “volunteering” (with the Junior League, the PTA and other civic and religious organizations) would hardly be called “sports” today, but they demanded appropriate outdoor clothing that balanced practicality with propriety—not least hats, gloves and parasols to ward off tans and freckles. Sometimes this inclusivity goes too far. “Modeling” seems like a flimsy excuse to include a fab trompe l’oeil Hermès dress; a “sightseeing” section includes a California-themed 1920s jacket that may or may not have been worn by a tourist. The provenance of a sailor dress by the nautically-minded Norman Norrell is impeccable, however; San Francisco socialite Clarissa Dyer wore it on vacation in Monaco in 1951.

Any history of sporting fashion in the West privileges wealthy—and, almost by default, white—women, who had more leisure time, more money to fund expensive recreational pursuits and custom-made clothes and more freedom to dress (and behave) unconventionally. In the exhibition’s catalog, sidebars on little-known sportswomen and their wardrobes help introduce women of color to the story, reminding readers “that actual people wore the clothing,” Jones says.

While today’s “outdoor girls” may cringe at the concept of basketball players in knee-length pantaloons, cheerleaders in ankle-length skirts or motorcyclists in mohair sweaters, these fashion advances were just as monumental as their wearers’ physical feats. Though the teamwork of fashion, feminism and female athletes has been overlooked for too long, “Sporting Fashion” settles the score.

“Sporting Fashion: Outdoor Girls, 1800-1960” is organized by the Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising and the American Federation of Arts, and shows July 24 – October 16, 2022, at the Dixon Gallery and Gardens, 4339 Park Avenue, Memphis, Tennessee 38117, with additional venues to come. Visit their website at www.dixon.org.

Additional touring locations:

FEBRUARY 11, 2023 TO MAY 7, 2023

Figge Art Museum

225 W 2nd Street

Davenport, Iowa 52801

www.figgeartmuseum.org

JUNE 17, 2023 TO SEPTEMBER 17, 2023

Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute

310 Genesee Street

Utica, New York 13502

www.mwpai.org

OCTOBER 14, 2023 TO JANUARY 14, 2024

Taft Museum of Art

316 Pike Street

Cincinnati, Ohio 45202

www.taftmuseum.org

FEBRUARY 24, 2024 TO MAY 19, 2024

Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens

829 Riverside Avenue

Jacksonville, Florida 32204

www.cummermuseum.org/visit/art/exhibition/sporting-fashion

FINAL LOCATION

FIDM Museum & Library

919 S Grand Avenue

Los Angeles, California 90015

www.fidmmuseum.org

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell is an LA-based fashion historian, curator and journalist and a frequent contributor to Ornament. Her impeccable ability to bring both humor and context to historical fashion enlivens each article she writes. The wide, wide world of sports is her topic for the current issue, just in time for the summer, as she explores how women’s sports fashion led the way for groundbreaking revolutions in both feminine style and textile technology. The impetus for this investigation is a traveling exhibition organized by the Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising Museum titled “Sporting Fashion: Outdoor Girls, 1800-1960”. Her book Skirts: Fashioning Modern Femininity in the 20th Century will be released by St. Martin’s Press in September 2022.